What’s the first thing you would do, if you had to build a distillery? Is it the grain? Should you go out and buy a copper still? Get the barrels? No, from time immemorial, the first question in any distillery of any kind is: where’s the water? Co-Founder, Jay Erisman, reveals what lies beneath the New Riff Distillery.

The very first thing we did, when Ken Lewis at The Party Source said “let’s do it! Let’s build a great distillery” was, we went looking for a superior source of water to Newport domestic tap. And, brothers and sisters, did we ever find it! If this distillery is a New Riff on an Old Tradition, then the well is the spindle on our long-playing turntable. Gaining the well changed everything in the design and operation of the distillery.

We knew we could run a perfectly good distillery on the municipal water supply servicing Newport, Kentucky. Nearly all the big distilleries in Kentucky run on municipal water. All the big Louisville distilleries use Louisville’s water (which is, quite rightly, very well regarded and is excellent tap water). Or they run on rivers. Buffalo Trace pulls their source water right out of the Kentucky River, and last we checked they were pretty much the most lauded distillery in the whole industry. The fabulous Four Roses plant makes some of the best Bourbon ever out of the Salt River. They all filter the river water, of course; or treat the municipal water to remove things like chlorine. But by and large, only a couple of them have an exclusive, special water source. (In the case of Louisville, in fact they all use an identical water source.) And they all make perfectly good whiskey. But we wanted to do better at New Riff, and furthermore we understand that every great whiskey distillery in the world is founded upon a unique and excellent water supply. And so, not being hydrologists by trade, we set about looking for one…and discovered it right beneath our feet!

The Aquifer

Directly beneath New Riff Distilling, under the land that Ken Lewis has owned since 1992, lies an aquifer. It’s called the Ohio River Alluvial Aquifer, and in fact it extends up and down the Ohio River, both sides, and is tapped by many light industries and some private clients for many years. It was created by the same glaciation that carved the Ohio River Valley. Doing our homework and research—which included consulting with hydrologists and water chemists at the University of Kentucky as well as historical sources, 1960-vintage geology and hydrology maps, and our own consultant Larry Ebersold—we determined that not only could we tap this aquifer for a robust water supply, but that it would be fantastic for making whiskey.

The aquifer water is clean, rich in flavor (for water, anyway), and very hard. The high concentration of calcium (what makes it so hard) indicates there is some limestone nearby, and in fact there is a source of limestone behind our aquifer. (Even though, as you’ll read below, we largely prefer to puncture the myth of “the limestone spring” from which great Bourbon grows. That is mostly a marketing gimmick spread by the large producers, all the more telling when they use domestic, ordinary water supplies for their production.) The aquifer is fed, over the eons, by two water sources:

- the secondary source is water from the Ohio River, over many years, seeping through the river bed through hundreds of feet of alluvial/glacial deposits (including clay, sand, and gravel) into the aquifer. There is a layer, almost like a “lip” of clay, in the river bank that is only semi-permeable to water and which somewhat impedes the flow of water from the river into the aquife

- the primary water source into the aquifer is groundwater from the hills to the south of the river (such as Fort Thomas). If you drive to New Riff from the south, you will go down a long hill to get here. These hills are underpinned by rich limestone deposits all over Campbell County; it’s the northern terminus of the huge limestone shelf that underlies all of the upper half of Kentucky. This highland groundwater flows downhill into the aquifer (see the graphic below).

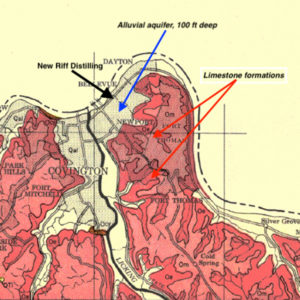

This 1960 groundwater map of Northern Kentucky clearly shows the disposition of geology and water sources in the area. New Riff lies in the region of the alluvial aquifer, which itself is influenced by the limestone formations lying immediately to the south.

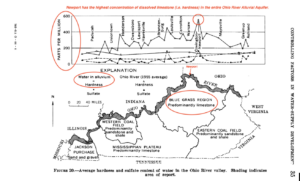

Thus, we don’t describe this as “a limestone aquifer,” because it was created by glaciation and is geologically composed of glacial fill right under the distillery. But the water in the aquifer is rich with limestone, thanks to the limestone deposits uphill to the south. In fact, our groundwater maps document that Newport is blessed with the the richest, densest water in the entire hundreds of miles of the Ohio River Alluvial Aquifer.

This 1966 report on Kentucky’s Ohio River Alluvial Hydrology documents that Newport has the highest concentration of dissolved limestone in the entire aquifer.

The well is also exceptionally well suited for making whiskey for two other reasons. First, it is quite a productive well, pushing out well over 500 gallons per minute of that great, clean hard water. The reason big distilleries can’t run on unique water supplies is they don’t supply enough water to make a bajillion barrels of whiskey every year. But New Riff is not big! We are just the perfect size to operate on 500 gallons per minute of water. You can’t run a giant whiskey plant on 500 GPM, but you can run a little jewel box of a plant like New Riff. Secondly—and this part was the other game changer for New Riff—our well is cold. The water is 58˚F, every single day of the year. And that temperature would have further ramifications, and benefits, for New Riff.

When you design a distillery, one of the critical parameters is the temperature of the process water. Throughout the whiskey making process, we are heating things up and cooling them down. Boiling the mash, then cooling it down to add malt. Steaming the beer, then condensing the alcoholic vapor with cooling water. All these processes hinge on cooling water. Most distilleries, running as they do on municipal water, see their water temps go up and down all year long. Furthermore, since every distillery requires large amounts of that cooling water, they have to expend large amounts of energy operating water cooling equipment in order to obtain that cool water. And they shut down in the summertime, when the water temperature exceeds their design parameters.

But New Riff doesn’t have that problem! We have no problem operating in the hottest Kentucky summer, thanks to our chilly well. Frankly, we weren’t totally sure what to expect from the well. We engineered the plant for 65˚F well water, we expected to find 62˚F. When we turned on the well for the first time, Jay Erisman asked the well engineer “What temp will it be, maybe about 62?” He replied with certainty, “Oh no, it’s 58 degrees.” Sure enough, we have 58˚F well water 24/7/365. And the well is a tremendous energy saver. We have only a small water chiller, to help us cool the hot mash down to below 70˚F for fermentation. Our hard-working all-copper condensers take their cooling water straight off the well, making for perfect consistency in condenser water temperature. (When other distillers visit, they ask “My goodness, don’t you regulate your condenser water temperature?” We reply, “Now, why would we do a damn fool thing like that? It’s perfect every day of the year.”)

Along with finding our master distiller consultant Larry Ebersold, this well was the most serendipitous part of the entire project. From Springbank on down, every great whiskey distillery has a great water supply. At New Riff, we discovered we had great water all along. Almost like, a great distillery was meant to happen right here…

The well provides for the water that goes in the mash and becomes whiskey, it handles all the cooling water for the distillery, but it does not feed the boiler, nor does it provide for dilution water in the barrel or the bottle. The boiler, for it’s part is fed by city water, which is softened before going to the boiler to become steam. The well water is too hard for this purpose, and would cause scaling in the boiler tubes as well as require a prohibitive amount of softening chemicals. For the water that cuts whiskey to barreling and bottling strength, we use reverse osmosis water for a neutral addition to the whiskey. We have produced a few experimental barrels that were cut with well water…we shall see what they turn into….

Learn more about the legendary Kentucky limestone springwater.